Forests, Flames, and Planes: Forest Protection, Wildland Fires, and Conservation

Visitors who come to New Brunswick are often struck by the vast forests and woodland across the province. These forests cover 88.4% of New Brunswick, a proportion larger than any other province in Canada.[1] These woodlands provide homes to wildlife, support industries in the province, and are a large part of New Brunswick’s identity. It includes both the Boreal and Acadian Forests, and it hosts a variety of trees, including but not limited to; white birch, black spruce, red oak, and red maple. [2] These diverse forests are integral to New Brunswick’s landscape and culture, and protecting and conserving them is essential.

Fire is a significant threat to the forests and the region’s people, but it also plays a significant role in maintaining the environment’s health. As climate change increasingly influences weather, with impacts on vegetation and human and animal health, it is vital to consider the role of wildland fire suppression in conservation. Combustion from fires accounts for one-fifth of the carbon from fossil fuels in Canada, and companies who suppress these fires play an active role in forest conservation in Canada.[3] Forest Protection Limited (FPL), based in New Brunswick, is one of these companies. Over the last sixty years, their aerial fire suppression helped preserve much of New Brunswick’s wildlands.

This paper uses Forest Protection Limited as an example to explore the connection between wildland fire suppression and conservation. Using research done by environmental historians, including Stephen Pyne and Richard A. Rajala, alongside government reports and documents from the FPL archive, this paper demonstrates the relationship between wildland fires and forests’ biodiversity, climate change, and soil nutrients. Wildland fires are both affected by and influence climate and environmental changes. The shifts in climates, including dryer weather and warmer temperatures, increase the frequency of fires. At the same time, when a wildland fire happens, the carbon stored in the forests is released into the atmosphere, which can adversely affect climate change. FPL’s work in fire suppression helps to stop unwanted fires and further protect the forests from fires in the future. In addition to these sources, FPL’s annual reports and other internal documentation were used to understand the role the company’s aerial fire suppression played in conservation. These documents gave insights into the company’s decision-making processes and the effectiveness of fire suppression each year. The researcher also looked for provincial and federal government reports and articles on wildland fire suppression to get a broader context of firefighting across Canada and understand New Brunswick’s and FPL’s roles. The documents revealed how aerial fire suppression helps preserve forests.

This paper argues that FPL’s wildland fire suppression operation was vital in conserving and protecting New Brunswick’s forests. It begins with a history of fire suppression in New Brunswick, starting with early tactics to control fires and the legislative acts that professionalized firefighting in the 1880s. It then outlines how methods advanced into the twentieth century to the 1950s and the founding of FPL. It provides insights into how wildland fire suppression became increasingly influential in forest protection. The second section outlines the historical connection between conservation and wildland fire suppression in Canada. It also discusses the effect wildland fires have and the forest’s ecosystems. FPL’s fire suppression operation fits how foresters and the public view fire and conservation. The third section outlines the history of FPL’s aerial firefighting in New Brunswick from its founding in 1952. This section not only shows the development of the company but also highlights the ways FPL actively protected New Brunswick’s forests. The paper’s final section demonstrates how FPL has aided conservation efforts in New Brunswick. FPL’s aerial fire suppression over the past sixty years is a part of the forest conservation efforts in New Brunswick. It will help protect New Brunswick’s forests and communities for future generations.

The Development of Wildland Fire Suppression in Canada

Although FPL has been guarding New Brunswick’s forests from fires for over half a century, a history of wildland fire suppression in Canada stretches back over two hundred years. Fire management strategies, such as selective burning, were first used by indigenous peoples to clear land, replenish soil nutrients, and reduce fire fuels. As the Saint John Inspector, Charles Morris, stated in 1761, “the highlands had generally been burned by Indians.”[4] This was a method of fire suppression to remove excess fuels from the area, create fire breaks, and stop accidental wildland fires. In the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, wildland fires confounded European newcomers, who saw them as “[o]bstacles to settlement.”[5] Selective burning fell out of favour in Canada as lumber became increasingly valuable. American Gifford Pinchot introduced settlers’ ideas about conservation in forestry. Pinchot first studied forestry in Germany, and after returning to the United States, he served as the Head of the Forestry Division from 1898 to 1901 and the Head of the United States Forest Service from 1901 to 1907. In these positions, he advocated for total fire suppression or the idea that all wildland fires must be stopped. In other words, he did not support selective burning. In the mind of Pinchot, the urgent need was to protect forests from the menace of unwanted fires, many of which were started by humans. For him, it meant stopping all fires so they could not get out of control. His efforts established this method across the United States and later Canada.[6]

In the late nineteenth century, the Canadian government took legislative steps to protect national forests and preserve the timber industry. Timber had become a significant export industry in Canada and was essential to the success of the colonies, especially New Brunswick. The intensive logging and lumber processing provided many jobs and brought wealth to the colony. In New Brunswick, the timber trade grew dramatically because Napoleon blockaded the Baltic from 1806-1811, which curtailed British trade with Europe.[7] This strengthened imperial economic ties to colonial forests. By the time of the Confederation in 1867, colonial governments saw forests as essential and wondered how best to protect them. As he crossed the country by rail in 1871, Prime Minister John A. MacDonald reflected on “the sight of immense masses of timber passing my windows every morning” and concluded that this spectre forced him to question “the unbound future of this great trade.”[8] MacDonald understood that the trees and forests were not an infinite resource and needed to be managed to maintain the industry. The New Brunswick government agreed. Over the last two decades of the 1800s, the colony established two necessary legislative acts to protect the forests. The 1885 Fire Act became the first fire law introducing burning restrictions from May to December. This act helped reduce the risk of wildland fires during the dry season. This was followed, in 1887, with legislation that provided funding to hire rangers and a Chief Fire Warden. It also allotted $2000 for salaries.[9] Establishing legislation and a system of enforcement was the New Brunswick government’s first steps to protect its essential forests from the threat of fires. Entering the twentieth century, wildland fire suppression in New Brunswick had become professionalized.

The additional money and authority given by the government to the Chief Fire Warden and his rangers aided in the development of better methods for fire suppression. In the early 1900s, the Forestry Branch used various hand tools to stop wildfires. They adapted equipment commonly used in farming and logging to create fire breaks and to smother fires. They employed crosscut saws, hatchets, shovels, and axes.[10] It was also common for firefighters to use wet blankets and sacks to starve fires of oxygen.[11] These fit squarely in the mainstream of early-twentieth-century fire suppression technologies, and many are still used by ground wildland firefighting crews today. Nonetheless, as the twentieth century progressed, advancements in communication and transportation also improved wildland firefighting. By the 1910s, fire services expanded telephone networks to communicate between fire towers. Installing these lines meant faster and more precise communication between the rangers at remote locations throughout the forests. In areas where telephone lines were inaccessible, the rangers relied on heliographs, which included a mirror with shutters on a tripod. It was used to communicate over long distances with Morse code.[12] Communication between the remote fire towers and stations was vital to respond to fires quickly. It also contributed to more successful suppression. But the addition of telephones and heliographs was not the only new technology that affected wildland fires and firefighting.

The development of railroads in Canada changed the cycle of wildland fires and how they were fought. By November 7, 1885, the railways connected people and goods nationwide. But rail also brought with it a threat of wildland fires. The coal-fueled trains required an active fire to run their combustion engines. These fires often created sparks that would escape the locomotive’s smokestacks. Unfortunately, these sparks sometimes caused wildland fires as the trains sped through the Canadian wilderness. The government in New Brunswick recognized this problem and the threat it posed to both communities and the timber trade should the fires get out of control. In 1912, the New Brunswick government set up a Board of Railway to make a fire suppression strategy, and they created programs to educate their employees on fire safety. This included looking for the signs of potential wildland fires.[13] The Canadian Pacific Railway removed fuel sources from rights-of-way and company property in other parts of Canada. By removing the fuels from these areas, the railways helped to stop the spread of accidental fires caused by stray sparks or burning coals coming off their trains. The lack of fuels meant the fires had nothing to burn and made fire breaks around the tracks. They inspected the trains, forbade employees from dropping live coals, patrolled the lands for fires, and requested that lumbermen and timbermen remove debris close to railway rights-of-way.[14] The railways also helped put out fires when they spotted them by sending out firefighting teams along the tracks (see Fig. 1 and 2). They also expanded fire suppression operations in the province and the country as a whole, and they educated the public on the importance of fire safety. Although railroads were the main culprit behind fire outbreaks in 1915, responsible for 65% of wildland fires, another 35% were started outside railway property. At the time, commentators believed these were likely begun by settlers’ logging activities, which the railway’s fire rangers did not monitor or control.[15] Yet, the changes to wildland fire fighting initiated by railways helped to promote innovation throughout the twentieth century.

Figure 1. Men fighting bushfire, sitting on railway tracks near Bala, Ontario, August 1916. (John Boyd, Library and Archives Canada, PA-69794).

Figure 2. Firefighting gang on a handcar, Bala, Ontario, August 1916. (John Boyd, Library and Archives Canada, PA-69793).

The twentieth century saw additional technological advancements in firefighting, which helped control fires more quickly and effectively. In addition to the telephone lines installed by railways for fire detection, the railways also added water pumps on all railcars. In 1911 and 1912, the Fairbanks-Morse Company created small portable water pumps that the Pacific Coast Logging Company installed on railway flatcars. These railcars allowed fire crews to move the pumps, which were way too heavy to be moved by man or horse on the road, along the rail lines to exactly where needed. The Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian North and Grand Trunk Railways followed suit by 1917.16 Although much more efficient, these water pumps had a limited range and were only employed on or around the rail tracks. Their limited use soon encouraged new approaches. Rather than trying to navigate the forests with water pumps by land, wildland firefighting moved to the sky.

The end of the First World War saw a surplus of aircraft decommissioned from service, and foresters began considering their use in fire patrol operations. Great Britain donated one hundred planes to Canada in June of 1919, which gave foresters and airlines the resources to initiate air operations for fire suppression and control. Using planes meant a broader scope of patrols and better forest surveys. By the end of the 1920s, Canada was leading the world in using aircraft for forest surveying and fire detection. [17] The Dominion Forestry Branch, the Canadian government department in charge of forestry, forest conservation, and research, used planes during fire surveying for the “detection of hitherto undiscovered fires” and “reconnaissance of known fires.”[18] The use of planes for aerial fire detection continued after the

Second World War. In New Brunswick, the Forest Service contracted a light Fleet of Avro Canada CF-100 planes for aerial patrols in 1947. This plane proved helpful for sketching and photographing wildland fires.[19] Using planes for aerial detection proved very successful, so Canadian foresters and firefighters looked to expand the application of planes, not just using them for finding fires but also for putting them out. As early as 1919, Canadian foresters were experimenting with ways to use planes to drop water on fires and to create fire breaks. They initially used lined paper bags filled with water that they dropped on fires. While some success was observed during these years, it was not until the postwar period that using air tankers for fire suppression became mainstream. These advancements in wildland fire techniques allowed foresters and wildland firefighters, including FPL, to manage fire threats better and protect the forests.

Wildland Fires and Conservation

Wildland fires not only threatened industries and communities but also had a significant effect on the environment. FPL’s wildland fire suppression in New Brunswick helped maintain the forests’ biodiversity and lessened the amount of carbon released into the air from burning woodlands. It is important to remember that fires are a part of the natural lifecycle of the forests. Each forest has a fire cycle, the natural time that elapses between fire events without human intervention.[20] This cycle is linked to and dependent on the weather of the region and its general climate. According to ecologist Erwin Wallace, the “[f]orest composition and structure strongly depend on the length of the regional fire cycles.”[21] Because of this relationship, it is essential to maintain the naturally occurring fire cycle for the health of the forests. Scientists have recorded changes in the fire cycles in Canada due to climate change.

As biologists Ève Lauzon, Yves Bergeron, Sylvie Gauthier, and Daniel Kneeshaw argued in 2011, “Climate change accounts for such variation in many regions where fire cycles have significantly increased since the end of the Little Ice Age (circa 1850).”[22] With fire frequency increasing due to climate change, it is even more critical for wildland fire suppression efforts to be effective and swift. In New Brunswick, FPL’s aerial fire suppression operations are an essential part of conservation in the province and protect the forests today and for the future. Although scientific understanding and study of climate change related to forest fires is relatively recent, people have connected the losses that forest fires cause any changes to the plants and soil in the affected areas since the late nineteenth century.

In the 1800s, conservation was often tied to industry and focused on maintaining timber supplies. The British government recognized the importance of forests to the economy and sought to ensure their protection by creating an “empire of forestry.” This was a type of conservation where the colonial government set aside certain land areas for unsettled forests. Canada adopted this type of conservation to preserve forests for the logging and timber trades. In 1884, the government instituted the Dominion Lands Act, which created a Canada-wide forest reserve system.[23] This system protected the crown’s timber and allowed for stronger forestry regulations. Because the forests were crown land, these rules could be more easily enforced, and the conservation of the forests more easily ensured. For example, the government regulated slash disposal on Dominion Land in 1915 to minimize accidental wildland fires. Slash is the woody debris left over from logging operations, which can fuel fires.[24] This type of early environmentalism and conservation remained focused on economic interests rather than concerns for the climate.

As forestry and wildland firefighting entered the second half of the twentieth century, a better understanding of the connections between fires and the environment developed. Scientists began to engage in conservation efforts for environmental rather than economic reasons.[25] Advancements in wildland firefighting methods and technology-focused attention on the prevalence of fires themselves and foresters and scientists began to question the connection between fires and weather (and, by extension, climate). Over the last twenty years, strong evidence has been presented to demonstrate the connection between wildland fire suppression and environmental protection. For example, scholars Sylvie Gauthier, Alan Leduc, Yves Bergeron, and Héloïse Le Goff argue that the lower annual burn rates in several regions in eastern Canada “compared to past rates seem to result from climate change and also in part from improved fire control strategies.” They suggest that “forest landscape fragmentation,” which has resulted “from agriculture and road network development, has increased accessibility and created fire breaks.”[26] These changes reveal the links among science, industry, climate, and fire suppression in forests. Because of studies like this, foresters can now look for the indicators of wildland fires, including a high burning index, high buildup level, low fuel moisture, and low relative humidity. The burn index refers to the estimated difficulty of putting out a fire, the buildup level is the number of fuel materials in an area, the fuel moisture is how dry that material is, and the relative humidity refers to the dryness in the surrounding air.[27] When there is a high burning index, high buildup level, low fuel moisture, and low relative humidity, the likelihood of a significant fire increases. If a fire does start, it can be devastating to the ecology of the forests in the region and have long-lasting implications for forests, including killing significant areas of the forests and increasing the risk for future fires.

Trees that escape being burned may still face destruction from fire because if they have their internal temperatures raised, they may also die even if they were not directly burned.[28] This means that many trees adjacent to a fire are killed and fuel future fires. In addition, trees that are burned in the fire negatively affect the forests because they drop debris into the water. At the same time, burned and dead trees serve as habitats for bugs, infecting healthy trees.[29] If not properly contained and managed, wildland forest fires can affect the forest for years to come and change the makeup of the ecosystem of the woods. FPL’s work to stop fires before they negatively affect the forests saves the trees currently threatened by fires and helps stop fires from happening in the future.

Trees are not the only life that is affected by wildland fires. The entire forest ecosystem can be in danger. According to scientists James McIver and Lyn Starr, “[n]umerous studies document how wildfire changes properties of the soil, which leads to changes in hydrology, erosion rates, stream characteristics, and vegetation growth.”[30] The soil’s properties then dictate the vegetation that grows, the topography of the landscape, and the layout of the forests. Fires can make soil water repellant, meaning the soil cannot support the indigenous plants in the forests.31 This stops the regrowth of the forests and illustrates the need for fire suppression to maintain healthy woods. Many foresters and environmentalists look to fire suppression companies to protect the forests and ensure a safe environment for the future. FPL did this for New Brunswick’s forests for over half a century and played an essential part in protecting the province’s forests and environment.

FPL’s History in Wildland Fire Suppression

As a New Brunswick Crown Entity established in September 1952, FPL’s mandate has been to preserve and protect the forests for the last seventy years. FPL is a global leader in full-spectrum forest health management and helps forest practitioners preserve and promote forest health through aerial firefighting, collaborative research & development, training, and aerial work. FPL is majority owned by the Province of New Brunswick (94%), and the other 6% is owned by forestry industry shareholders in New Brunswick. Its headquarters has always been the provincial capital of Fredericton, and it has operated throughout the province of New Brunswick, as well as other provinces in Canada, including British Columbia, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec. FPL has also operated internationally throughout the United States, including in Maine, Idaho, Washington, Montana, and Florida.

FPL initially engaged in aerial spruce budworm control and management (see Fig. 3). In 1952, the company used five airstrips across the province: Charlo, Bathurst, Kedgwick, Boston Brook, and Tobique. FPL would add additional airstrips as the company grew in the second half of the twentieth century. These airstrips let the planes and pilots have adequate access across the province and allowed FPL to participate in the world’s most extensive aerial insect control program by 1957. It was a joint operation between two provinces, New Brunswick and Quebec. It was named Operation Budworm #6 in New Brunswick and #4 in Quebec. By its completion, the program had employed one hundred and fifteen aircraft and twenty-two airstrips.[32] This massive program in the 1950s helped to develop the methods used by FPL and developed the skills later used for fire suppression in New Brunswick.

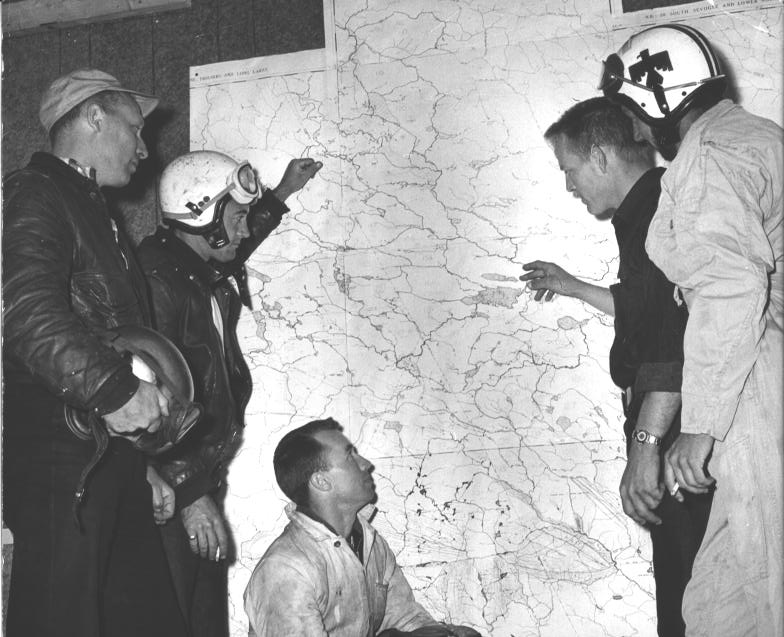

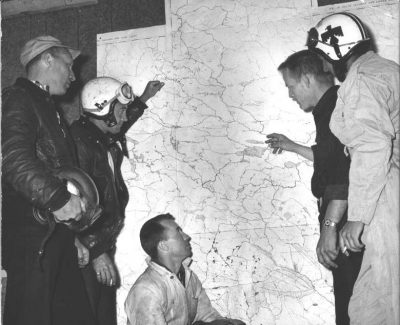

Figure 3. FPL pilots checking maps for aerial insect control operations in New Brunswick c. 1952. (Photo, c. 1952, Forest Protection Limited Archives).

By 1960, FPL began the business of aerial forest fire suppression. In the summer of 1960, the province of New Brunswick contracted FPL to drop water on a fire burning in a previously logged area. At the time, FPL sent four Grumman T. B. M. aircraft. These were planes the company more commonly used for insect control. While it was a successful first fire suppression mission, FPL had yet to take on a more prominent role in fire suppression in the province. That said, FPL did fund experiments to find the best methods of aerial fire suppression for New Brunswick. In the 1961 Board of Director Meeting Minutes, Forest Ranger B. F. Flieger reported: “on aerial water dropping experiments, the cost of which amounted to less than $10,000.”[33] These experiments show FPL’s dedication, in the early 1960s, to providing excellent wildland fire suppression and preserving New Brunswick’s forests. Although the company did work to develop their fire suppression methods, it did not get an opportunity to use them again for five years.

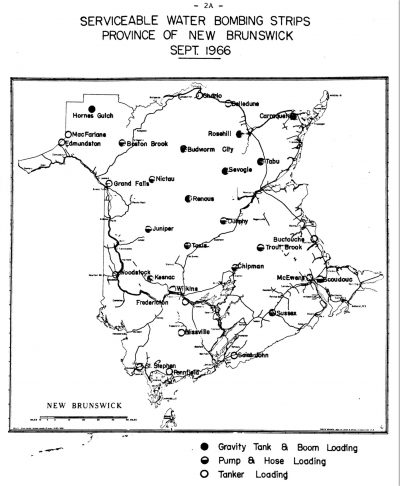

In 1966 the New Brunswick government contracted FPL for fire suppression on an operational and ongoing basis. [34] FPL used their network of planes and airstrips to provide services to the entire province and ensure fast deployment of their resources (see Fig. 4). Although FPL already had various airstrips in use for insect control operations, they needed to be outfitted for fire suppression operations. This included adding water tanks and pumps to each airstrip for fast tanker refilling. At this time, refueling and refilling the tanks was accomplished by handpumps, which was a slow process but worked even in emergencies when electricity went out. The operations were headquartered at Dunphy Airstrip in Upper Blackville, NB, because, “it was centrally located and offered both sleeping and eating accommodations plus a 2900’ paved runway.”[35] This was important as the pilots would stay onsite during their shifts to respond to fires as soon as they were reported quickly.

From May 24 – September 14, 1966, FPL was dispatched to 31 fires, flew 386 hours, and helped stop fires from burning on 2,349.25 acres. Speaking about a fire that occurred on July 17, 1966, Flieger stated, “Another point that makes me believe the water bombing held the fire is that the burn was very patchy and a lot of the fire spread on the ground and did not get in the trees or the crown. I was very well pleased with the help we received from the water bombers.”[36] This quote highlights the success of this early operation and the effect it had on protecting New Brunswick’s forests. While FPL’s operations helped minimize the damage to New Brunswick’s forests, the province did not routinely use FPL’s services again until the mid-1970s.[37] In the meantime, FPL acquired more planes. By 1971, FPL had the world’s largest civilian fleet of T.B.M. Avengers with 43 aircraft, although not used for fire suppression but for insect control.[38] With this fleet, the company began considering other uses for their aircraft.

Figure 4. Aerial fire suppression airstrips were used in New Brunswick in 1966. (B. B. Meadows, Water Bombing Operations in New Brunswick 1966, Fredericton: Department of Natural Resources, 1966).

At the August 7, 1975, Board of Directors Meeting, the board agreed that the Managing Director of FPL would talk to the Deputy Minister of Natural Resources about contracting the company for aerial fire suppression and patrols.[39] It had been almost ten years since the FPL’s last contract for fire suppression operations, and the board agreed that they were the right company to provide this service in New Brunswick as the insect control program ended before the fire season. Hence, they had the planes and personnel available. FPL contacted the Department of Natural Resources, suggesting they use the insect control aircraft for fire suppression once the insect control program finished for the year. The province agreed and in 1976, FPL restarted their fire suppression operations. The company supplied the fully equipped aircraft, maintenance, pilots, and administration, and the government provided employees’ room and board, fuel, and oil for the planes. [40] By June 29, 1976, FPL was preparing six T.B.M. Avengers for fire suppression.[41] Converting each plane from insect control to fire suppression cost the company $2,000 per plane. The total cost was $12,000.[42] This investment proved to be a good choice, and by 1978, FPL added three additional air tankers to their fire suppression fleet bringing the total number to nine. They also added four support aircraft (see Fig. 5).[43] That year, the air tanker fleet flew 281 hours from August 5th to September 7th.[44] The fire suppression program at FPL saw itself growing in the 1970s but ceased operations in the 1980s as the New Brunswick government and FPL renegotiated the budget for fire suppression operations.[45] While this was the case, once fire suppression efforts began in the 1990s, FPL again became integral to stopping wildland fires in New Brunswick.

In 1991, FPL started doing aerial fire suppression for the New Brunswick government yet again. This time the program grew even more extensive. In 1991 when FPL restarted fire suppression, they converted seven planes at the cost of about $500,000, which was paid by the province.[46] While this was a substantial fleet, FPL converted four more aircraft the following year.[47] The fleet did not stop growing, and by 1993, twelve T.B.M. Avengers were modified for fire suppression.[48] Having this many aircraft ready for fire suppression meant that FPL could quickly deal with small and large fires across the province and quickly stop the damage to the province’s environment. While T.B.M. Avengers had their first life as torpedo bombers, FPL used them for aerial treatment and fire suppression. Once converted, the T.B.M. Avengers had one seat and a 625 US-gallon tank in the former bomb bay. This large fleet ensured a fast response time to fires, and in 1997, it only took FPL twenty-two minutes to respond to fire once the call was received.[49] A quick response time was essential to stopping fires from spreading and conserving New Brunswick’s forests. Over time, the T.B.M. Avengers became harder to maintain and FPL invested in new aircraft.

Figure 5. Some of the T.B.M Avengers Aircraft used by FPL in aerial insect control and fire suppression operations, Fredericton, NB, 1979. (TBM#8 #2 #3 #4 #19, A2-66, Forest Protection Limited Archives).

Figure 6. Forest Protection Limited’s AT-802 (front) and a T.B.M. Avenger (back) flying together (K. Marshall, AT802#20 and TBM#24 Airborne Together, April 1, 2001, Forest Protection Limited Archives).

In 2001, FPL leased their first Air Tractor 802 (AT802) to work alongside the T.B.M. Avengers (see Fig. 6). AT-802s were agricultural aircraft that were adapted for fire fighting. First manufactured in 1990, the plane has an 820 US gallon tank between the engine firewall and the cockpit. They were the world’s largest single-engine air tankers and could be used for aerial fire fighting and aerial insect treatment missions. By 2003, FPL owned six of these planes.[50] To make the AT-802s even more efficient for fire suppression, the company installed FireNav systems in all their tankers in 2004. This system allowed the company to track all planes simultaneously, provided air collision warnings around a fire, mapped the fire area, and provided superior navigation to the fire.[51] The advancement in fire suppression aircraft and technology meant New Brunswick saw every area annually. Each year, from 1992 to 2002, less than 1000 hectares of land were burned. As a director of FPL commented in the Board of Directors meeting on October 8, 2002, “These were impressive numbers.”[52]

FPL’s fire suppression efforts in the second half of the twentieth century reflected a larger shift to modern environmentalism, which focused on pollution, health, and work safety.[53] Across Canada, wildland fire threatens twenty communities and 70,000 people annually, costing about $700 million for fire management.[54] Not only do these fires devastate communities and endanger people and property, but they also threaten the environment. As climate change increases the number of fires, carbon stored in the forests is released into the atmosphere.[55] FPL plays a vital role in preserving the provinces’ environment and climate by stopping these fires from growing in New Brunswick.

FPL, Fire Suppression, and Conservation

New Brunswick has 27,835 square miles of coniferous, deciduous, and mixed forests that are important to the province’s landscape, economy, and society.[56] The forestry sector is a significant contributor to provincial taxes and exports, employs thousands of people in New Brunswick and has done so for many years. In 1988, forestry generated $25.2 million in provincial taxes, produced exports valued at $2.1 billion or 44.9% of total exports, and employed approximately 33,000 people.[57] NB forests continue to be important in the province today, but climate change threatens them. The Acadian forests that cover most of New Brunswick are ancient and have developed for over 10,000 years since the retreat of the last glacier. The World Wildlife Fund now counts the Acadian Forest among the most endangered in North America.[58] Helping to protect these forests from the damage and loss caused by wildland fires is imperative to save them for future generations. FPL has played a large part in this.

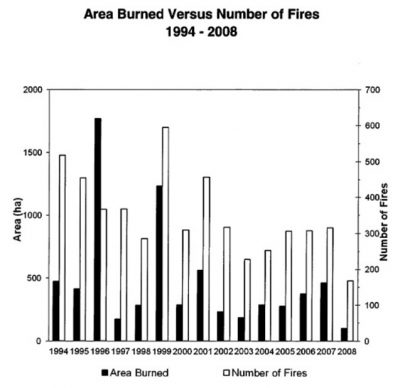

From 1920 to 1975, before FPL’s yearly fire suppression operations, the average area burned yearly from wildfires was 12,000 hectares.[59] Although this number may not seem high, losing forests and animal habitats was detrimental to the province’s ecosystem and contributed to climate change. FPL’s intervention significantly reduced the area burned because of its ability to quickly respond and control wildland fires. From 1994 to 2008, by contrast, the average area burned in New Brunswick was less than 500 hectares (See Fig. 7). This is a significant reduction in the size of fires in the province. Even in the first year of FPL’s continued fire suppression operations in 1975, the average size of fires in New Brunswick went from twenty hectares to just four.[60] By 1990, 46% of wildland fires in New Brunswick grew less than one hectare after the initial attack. On top of this, 45% of fires were under control the day they started and 71% in less than two days. Even more impressive is that approximately 20% were under control within thirty minutes. The efficiency of FPL’s fire suppression meant that almost half of all wildland fires only required one round of fire suppressant to control. [61] The fire suppression done by FPL over the last sixty years in New Brunswick has significantly contributed to the conservation of the province’s forests. FPL’s aerial fire suppression has lowered the size and duration of wildland fires, stopping the destruction of natural animal habitats, saving communities, and positively affecting climate change in New Brunswick.

FPL is a part of the long history of wildland fire suppression in North America. This started with conservation efforts to preserve the crown timber and logging trade, grew into suppression efforts run by the railways, and led to modern environmentalism focused on climate change. The growth of firefighting technology and machinery helped to control fires more quickly and safely. The introduction of telephone lines for faster communication in the late nineteenth century, portable water pumps in the 1910s, and aerial firefighting in the postwar period created fire suppression methods that helped protect the forests’ critical ecosystems.

Over FPL’s sixty years of providing aerial fire suppression for New Brunswick, the company has grown their fleet. It provides fire suppression across the province in approximately twenty minutes, stopping fires from growing and destroying the vegetation and soil of the forests. FPL’s continued commitment to having the best-suited aircraft and technology for fire suppression lowers the threat of fire across the province. When New Brunswickers see the FPL planes flying overhead and dropping the vibrant red fire suppressants on our forests (see Fig. 8), they can feel assured that the company is protecting the province’s forests for future generations.

Figure 7. The area burned versus the number of fires in New Brunswick from 1994 to 2008. (Forest Protection Limited 2008 Management Plan, March 2014, pg. 6, Forest Protection Limited Archives).

Figure 8. Air tankers drop a fire retardant on the woods off Riverglade Road, west of Moncton, May 8, 2012. (Photo, Forest Protection Limited Archives).

Bibliography

PRIMARY SOURCES

1952-FPL’s 60th Anniversary. Lincoln, NB: Forest Protection Limited, July 2012.

Climate Change and Fire Management Research Strategy. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Forests and Range Wildfire Management, 2009.

Forest Protection Limited. Annual Reports. 1952-2013. Forest Protection Limited Archives.

———. Board of Directors Meeting Minutes. 1952-2019. Forest Protection Limited Archives.

———. Correspondence. 2008-2021. Forest Protection Limited Archives.

MacTier, A. D. Fire Protection from the Standpoint of Railways. Ottawa: Commission of Conservation Canada, 1915.

Meadows, B. B. Water Bombing Operations in New Brunswick 1966. Fredericton: Department of Natural Resources, 1966.

The Province of New Brunswick. Report of the Forest Resources Study. New Brunswick: 1974.

R/EMS Research LTD. Evaluation of Fire Control of New Brunswick: An Unsolicited Contract Proposal. Fredericton: 1988.

White, J. H. “Forestry on Dominion Lands.” Forest Protection in Canada, 1913-1914. Ottawa: Commission of Conservation, 1915.

BOOKS

Arno, Stephen F. and Stephen Allison-Burnell. Flames in Our Forest: Disaster or Renewal? Washington: Island Press, 2002.

Barton, Greg. Empire Forestry and the Origins of Environmentalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Bisson, B.G. and C. C. Bursey. Evaluation of Forest Fire Suppression in New Brunswick: A Retrospective Analysis. Fredericton: University of New Brunswick, May-Oct. 1990.

Davis, Kenneth P. Forest Fire: Control and Use. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1959.

DeWolfe, Karen, David Coon, and Inuk Simard. Our Acadian Forests are in Danger: The State of Forest Diversity and Wildlife Habitat in New Brunswick. Fredericton: The Conservation Council of New Brunswick, 2005.

Lauzon, Ève, Yves Bergeron, Sylvie Gauthier, and Daniel Kneeshaw. Fire Cycles and Forest Management: An Alternative Approach for Management of Canadian Boreal Forests. Canada: Sustainable Forest Management Network, 2006.

MacEachern, Alan. The Miramichi Fire: A History. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020.

McIver, James and Lynn Starr, Eds. Environmental Effects of Positive Logging: Literature Review with Annotated Bibliography. Portland: United States Department of Agricultural, Forest Services, 2000.

Perera, Ajith H., Lisa J. Buse, and Michael G. Weber. Emulating Natural Forest Landscapes

Disturbances: Concepts and Applications. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Pyne, Stephen J. Awful Splendour: A Fire History of Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2007.

Rajala, Richard A. Feds, Forests, and Fire: A Century of Canadian Forest Innovation. Ottawa: Canadian Science and Technology Museum, 2005.

Seto, William. A History of Forest Protection Limited (1952-1992): To Protect Forests. Fredericton: FPL, 1992.

Wallace, Erwin B. Woodlands: Ecology, Management, and Conservation. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2011.

ARTICLES

Gauthier, Sylvie, Alan Leduc, Yves Bergeron, and Héloïse Le Goff, “Fire Frequencies and

Forest Management Based on Natural Disturbances.” In Ecosystem Management in the Boreal Forest, edited by Sylvie Gauthier, 59-77. Laval: University of Quebec Press, 2009.

Harding, Stephen. “Northern Avengers.” Warbirds International 12 no. 4 (July/Aug. 1993): 4 -11.

Ogden, A. E., and J. Innes. “Incorporating Clime Change Adaptation Considerations into Forest Management Planning in the Boreal Forests.” The International Forestry Review 9 no. 3 (Sept. 2007): 713-733.

Owen, Jane. “Garden Gear: Mattocks.” Financial Times 13 (2008): 13.

Stanton, C. R. and R. J. Bourchier. “Forest Regions.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Last Modified Mar. 20, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/forest -regions.

Wein, Ross W. and Janice M. Moore. “Fire History and Rotation in the New Brunswick Acadian Forest.” Canadian Journal of Forest Research 7 no. 2 (1977): 285-294.